The new role of cities in our society.

Almost 75% of Europeans live in cities nowadays. At the same time, cities are becoming a crucial transnational governance level. They are organising themselves in a whole tissue of networks, like Eurocities, Fearless Cities or Energycities, working together in domains like climate policy, renewable energy and urban economy. Especially in cities with a progressive government – not seldom with Greens in power – the most ambitious future strategy plans are introduced (e.g. the Helsinki city council decided to become carbon-neutral by 2035), going beyond what is thought possible at the national level. Interestingly, also the strategic vision of the European Union has an increasingly clear urban dimension and recognises the potential and capacity of Europe’s cities to deliver on objectives like jobs, migration, climate, energy and the digital and the circular economy. This creates new possibilities for the work of these city networks, as they – through a bottom-up approach – respond to common issues that affect the day-to-day lives of Europeans. Eurocities for example, was founded in 1986 by the mayors of Barcelona, Birmingham, Frankfurt, Lyon, Milan and Rotterdam. It aims to put cities forward as drivers of quality jobs and sustainable growth, as inclusive, diverse and creative; as green and healthy, as smarter and innovative. To do so, it offers platforms for sharing knowledge and exchanging ideas (e.g. thematic forums, working groups, projects, activities, events) in domains like culture, economy, environment and mobility. Today, Eurocities brings together the local governments of over 140 of Europe’s largest cities and over 45 partner cities.

Energy Cities is the European Association of local authorities in energy transition, representing more than 1,000 towns and cities in 30 countries. It aims to strengthen their role and skills in the field of sustainable energy, to represent their interests and influence the policies and proposals made by EU institutions in the fields of energy, environmental protection and urban policy. Furthermore, it strives to develop and promote their initiatives through exchange of experiences, the transfer of knowhow and the implementation of joint projects.

Another network example is Fearless Cities, a global municipalist movement that stands up to defend human rights, democracy and the common good. It organises international summits that allow municipalist movements to build global networks of solidarity and hope in the face of hate, walls and borders. The first fearless cities event was organised by Barcelona en Comú in 2017. Through participatory methods, it aims to inspire people to reflect on democracy, and to create new synergies to take their efforts to the next level.

These networks and strategy plans reflect a broader change in what is happening within cities. The dominant picture on the national level, that only public authorities and market forces seem important, is challenged by developments on the city level, where more and more citizens’ initiatives or commons arise, focusing on co-operation with and among citizens, and inspired by ethics of care. Tired of being only a consumer (depending on what the market has to offer) or a passive citizen (expecting everything of the elected politicians), people become active as maker, designer, urban farmer, solidarity volunteer, user of shared resources such as cars or bikes, civic or social entrepreneur, and more. This goes hand in hand with the founding of new organisations, infrastructures and open access resources like digital platforms for the sharing economy, fablabs, energy co-ops, co-working spaces, urban food production plots, etc. Collaboration and participation are important qualities of these new developments. Also, one can see their convergence with the existing cooperative, social and solidarity economy.1

Urban commons transitions.

In recent years, we have seen some cities move one step further as they develop specific structures and processes that, in a thoughtful manner, aim at building synergies between the public and the commons domain. They transform themselves into a so-called enabling or Partner State. In this new perspective, politicians do not see their political constituency as a territory to manage from above, but as a community of citizens with a lot of experience and creativity. So instead of top-down politics, they develop forms of co-creation and co-production. In Ghent for instance, citizens developed the concept of ‘living streets’: they wanted to reclaim their streets, strengthen the sense of ‘neighbourliness’ and dismiss cars for one or two months a year. The city government took all the measures needed to make it happen in a legal and safe way. If local government had conducted this experiment unilaterally it would have provoked enormous protest. Through these public-civil partnerships however, an underestimated area of societal possibilities can be explored in a positive way.

This is part of a new political vision, where the government considers itself as a partner of its citizens and associations and takes the concerns of every citizen serious: A democratic state of the 21st century that steers a mixed economy, regulates markets properly and gives incentives to alternative economic institutions, like the commons and cooperatives.2

Merging these developments could lead to a prototype of transformative cities as a driving force towards a socio-ecological society. The City of Bologna (amongst other Italian cities) is a strong example of how new institutional processes for public-civil partnerships can be developed. In 2014, the city published the ‘Bologna Regulation on Public Collaboration for Urban Commons’, whereby Urban Commons are described as ‘the goods – tangible, intangible and digital – that citizens and the Administration – also through participative and deliberative procedures – recognise to be functional to the individual and collective well-being, so they can share the responsibility of their care or regeneration in order to improve the collective enjoyment. The collaboration among citizens and the Administration is based on 1) mutual trust, 2) publicity and transparency, 3) responsibility, 4) inclusiveness and openness, 5) sustainability, 6) proportionality, 7) adequacy and differentiation, 8) informality and 9) civic autonomy.

Building on these experiences, commons expert Michel Bauwens wrote a Strategic Commons Transition Plan for the city of Ghent.3 In this report, the author develops coherent proposals for new forms of cooperation between local authorities and citizens’ initiatives.

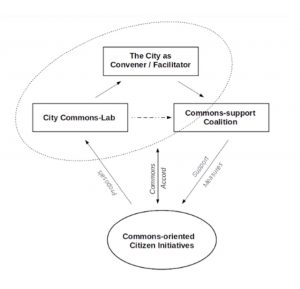

1. The first is a clear structure that installs a supportive relationship between the city government and people running and participating in citizens’ or commons initiatives. Bauwens proposes the creation of a City Lab that helps people develop their proposals and prepares Commons Agreements between the city and the new initiatives, modelled after the existing Bologna Regulation on Commons. Equally important is the establishment of support-coalitions for every commons: which are the actors in the city that can support an initiative? (Those can be public, private and civil organisations.)

2. Second, citizens’ initiatives or commons should play a key role in the transition towards a resilient city. This, however, requires people participating in the commons to have a greater voice in the city. Bauwens proposes the establishment of two new institutions: the Assembly of the Commons, for all citizens active in commons’ initiatives, and the Chamber of the Commons, for all social entrepreneurs creating livelihoods around these commons. These new institutions are necessary because people active in commons initiatives work using a contributive logic. This means people are not looking to extract value (having private profit as central goal) but want to generate social value in the first place.

3. Last but not least, people who want to engage in the commons should be provided with the same support as a mainstream profit-driven start-up. This entails at least three things: the creation of an incubator for a commons-based economy, the establishment of new urban finance mechanisms (e.g. a public city bank), and the development of mutualized commons infrastructures through inter-city cooperation (e.g. Fairbnb as alternative for Airbnb).

Co-cities: collaborative cities – design for commons

We find a similar inspiring approach in the international CoCity Project from LabGov (collaborative cities-design for commons).4 LabGov has investigated new forms of collaborative city-making that ‘are leading urban areas towards new forms of participatory urban governance, inclusive economic growth and social innovation. The project takes urban commons as a starting point. As the researchers state, “a ‘CoCity’ is based on urban co-governance which implies shared, collaborative, polycentric governance of the urban commons and in which environmental, cultural, knowledge and digital urban resources are co-managed through contractual or institutionalized public-private-community partnerships.

Urban commons in a Co-City are governed in a shared, collaborative, polycentric way involving different forms of resource pooling and cooperation between 1) social innovators (i.e. active citizens, city makers, digital collaboratives, urban regenerators, community gardeners, etc.), 2) public authorities, 3) businesses, 4) civil society organisations, and 5) knowledge institutions (i.e. schools, universities, cultural institutions, museums, academies, etc.). Public authorities play an important enabling role in creating and sustaining the cocity in order to make it more just and democratic.“5

On the basis of the principles that the Nobel prize Winner Elinor Ostrom identified as characteristic for commons, combined with their own research findings, the people of Co-Cities defined 5 key design principles for Urban Commons:

Principle 1: Collective governance refers to the presence of a multi-stakeholder governance scheme whereby the community emerges as an actor and partners up with at least three different urban actors

Principle 2: Enabling State expresses the role of the State in facilitating the creation of urban commons and supporting collective action arrangements for the management and sustainability of the urban commons.

Principle 3: Social and Economic Pooling refers to the presence of different forms of resource pooling and cooperation between five possible actors in the urban environment

Principle 4: Experimentalism is the presence of an adaptive and iterative approach to designing the legal processes and institutions that govern urban commons.

Principle 5: Tech Justice highlights access to technology, the presence of digital infrastructure, and open data protocols as an enabling driver of collaboration and the creation of urban commons.

Finally, in the Co-City Project, two core principles are identified underlying a co-city: the enabling state (quite similar as the above defined partner state) and pooling economies. The end of 2018, LabGov published several very relevant publications, including a “Co-Cities report”. This report measured the existence of Co-City design principles in a database of 400+ case studies in 130+ cities around the world. It convincingly shows how cities are implementing the right to the city through co-governance.6

Productive cities and pooling economies: design global, produce local.

To really make the transition happen, commons have to become productive. So, we have to move to a new level, from the level of sharing (or mutualising) our infrastructure (car-sharing, co-housing, etc.) to the next level of being productive themselves. This connects the actual changes with the utopian vision of an evolution towards a post-capitalist mode of exchange and production, or at least a mixed economy. This requires new ways of organising provision systems and the turning crucial infrastructures into commons (or ‘commonification’). Think about digital platforms used worldwide, combined with localised shared economy initiatives such as co-working spaces, that can be the catalyst of what Michel Bauwens describes as “cosmo-local production, combining globally shared productive knowledge with relocalized production capacities through the technology linked to distributed manufacturing”. To make it concrete, take the example of the Valori wooden chair designed by Denis Fuzil in Sao Paulo, and distributed by London based Open Desk. If you want to buy the chair, Open Desk will help you to find a local workshop that will produce it close to your home. Something extraordinary? Not really, the chair now has been produced more than 10.000 times in more than half the countries in the world. These types of open design communities can be the alternative to the current dominant mode of innovation, based on patents and copyrights.

Leagues of cities.

The real societal change will only occur if cities work together, not just in loose networks, but really forming a League of Commons Cities with a shared goal. This can include the co-development of global open source infrastructures that are needed to solve systemic issues that affect all cities. As an example, consider Munibnb or Fairbnb, coalitions developing alternative solutions to Airbnb. FairBnB is at this moment firstly a community of activists, coders, researchers and designers that wants to offer a community-centred alternative to commercial platforms, prioritises people over profit and facilitates authentic and sustainable travel experiences, while minimising the cost to communities. This is done on the basis of the principles of collective ownership, democratic governance, social sustainability, transparency and accountability.

Another relevant development is the movement of cities that want to evolve from fablabs to fabcities. This initiative, Fab City, aims at a new urban model for self-sufficient cities. The project, initiated by institutes in Spain and the US, involves cities such as Barcelona (Spain), Kerala (India) and Shenzhen (China). Fab City aims to empower citizens with micro factories in every neighbourhood to allow for a drastic reduction of energy consumption and of transportation of materials and goods. The goal is to develop locally productive and globally connected self-sufficient cities by 2054. Hence, cities produce everything they consume; with a global repository of open source designs for city solutions.

Building coalitions for the future.

As the Green European Foundation has stated earlier, it is true that ‘we see too little progress in the critical fight against climate change and for the construction of a truly sustainable economic and social system’. But this analysis neglects at the same time new powerful developments in frontrunner cities. At this level, exciting possibilities exist to build synergies with actors developing innovative initiatives, giving the growing field of social entrepreneurs, new business models and public-commons partnerships.

There is a clear need to create platforms that bring together, from all over Europe, political, civil and economic actors (cf. the five actors mentioned in the Co-Cities project above) from progressive cities developing transformative policies. This would make it possible, founded on concrete policies and project, to communicate a legitimate and positive picture of Europe. It can raise political awareness of the importance of progressive city networks.

ENDNOTES

1 Interview with Christian Iaione: Poolism: sharing economy vs. pooling economy https://blog.p2pfoundation.net/ poolism-sharing-economy-vs-pooling-economy/2016/07/06

2 Holemans D. Freedom & Security in a Complex World. Green European Foundation, Brussels, 2017: available at http://gef. eu/publication/freedom-security

3 Holemans D. How New Institutions Can Bolster Ghent’s Commons Initiatives https://www.shareable.net/blog/how-newinstitutions-can-make-ghent-a-commons-city

4 http://collaborativecities.designforcommons.org

5 http://collaborativecities.designforcommons.org

6 http://labgov.city/co-city-protocol/the-co-cities-open-book

Download

Download here the pdf-version of this paper.

Creating Socio-Ecological Societies Through Urban Commons Transitions. Dirk Holemans & Kati Van de Velde. Publ. Green European Foundation in collaboration with Oikos. 2019

Recent Comments